Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508-12

Disclaimer: This post has nudity, and that’s something to be ashamed of. Just ask Eve.

I like to think of myself as a weekend art historian. I’m no scholar, but I know a few things, and I love love love studying art history. This is my blog, and I can be a big nerd if I want to, so I’m going to.

This is the first in a series of monthly posts about paintings that tell stories, drawing from my ‘Stories in Art‘ project. As the great Maria von Trapp once said, “Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start.” Sorry to start things off with a really corny quote, but as you will see, artists always quote stuff they love.

Adam and Eve

“In the beginning” God created the world, including the first man and the first woman. If you read through a few more books of the Old Testament and do the math, this happened about 6,000 years ago, which doesn’t make any sense AT ALL, but we can talk about that later.

Anyway, Genesis chapter 2 tells the story of Adam and Eve, and we turn to our old friend Michelangelo for some visual references. First, the Creation of Adam, and then the Creation of Eve from one of Adam’s ribs. Then, in chapter 3, things got weird. Anyone who has had some trouble following instructions can identify with this part of the story. God said don’t eat, and Eve ate. Thanks Eve.

This began a long history of paintings that illustrate a simple but destructive notion: “women can’t be trusted.” Check out this painting by Johann Loth (below). This celebration of skin tones tells a simple story: She’s hot, but she’s trouble.

Click on Loth’s painting on the right, then click on Loth’s name (top left) to see some of his other images of strong female biblical characters turned into dangerous temptresses. Thanks Loth.

So, Adam and Eve got kicked out of the Garden of Eden, and this scene (known as “The Expulsion” in art history) became important to a series of artistic “quotations”. When a writer tries to show that he is well-read, he makes reference to well-known literary masters. It’s the same thing with art history. In the Renaissance and Baroque eras, when an artist was trying to make a name for himself, he would deliberately make the viewer think of a famous masterpiece by incorporating a well-known scene into his work.

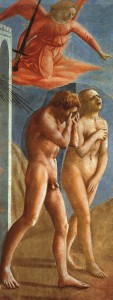

In a little chapel in an out-of-the-way church in Florence, the early Renaissance artist Masaccio frescoed the scene of The Expulsion (1426-7) (below). It may look ‘primitive’ to us, but at the time, the scene’s raw emotion was so captivating, that other artists began to ‘quote’ this scene. In Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise (1425-52), a similar version of this scene can be found in the bottom-right of the Garden of Eden panel (below). Michelangelo’s scene on Sistine Chapel Ceiling (1508-12) is also reminiscent of his fellow Florentine’s depiction.

Masaccio was also quoting a previous master, and Michelangelo’s Expulsion was also famously quoted. One of the most influential sculptures from antiquity is a sculpture of Venus where the Goddess of Love covers herself with her arms rather than standing triumphantly like a male god. Masaccio recognized that this gesture of modesty applies perfectly to Eve and her revelation that nudity is shameful.

This ancient Greek sculpture was known by many Roman copies, so Masaccio could have easily been aware of it. In fact, it’s possible that he was familiar with the most famous copy, The Medici Venus, owned by the Florentines for many centuries.

Fast forward to 1610 when the Baroque era was in its infancy, and so was the career of Artemisia Gentileschi. If male artists quote other artists to show that they know what they’re doing, then female artists needed to do so twice as much, especially when the live in a ‘library’ like Rome. Gentileschi’s father took his young talented daughter all over Rome to see the famous frescoes, especially the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. In one of Gentileschi’s early works, Susanna and the Elders (1610), she quoted Michelangelo’s Expulsion by reversing Adam’s defensive gesture. Susanna was spied upon while bathing, and in the same way that Masaccio saw Eve in a sculpture of Venus, Gentileschi saw Susanna in Adam’s anguished objection to being expelled.

Don’t get me started on Susanna, but it was not her fault that those guys were spying on her and they deserved their punishment when the truth was finally discovered (Thanks Daniel). Same as with depictions of Eve, artists have spun Susanna’s story to make it look like she was far from innocent. This brings us full circle back to Eve, her ‘mistake’, and the notion that women can’t be trusted because they are temptresses who are just trying to lure you into big trouble. Biblical stories of women were spun by artists to downplay the importance of the woman’s role in the story, and to draw attention to the horrible fate of man if he trusts a woman. Suckers.

Masaccio’s The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, 1426-7

Lorenzo Ghiberti’s The Expulsion, detail from the ‘Garden of Eden’ panel on the Gates of Paradise, Baptistry of St. John, Florence, 1425-52