Stories in Art: Rebekah at the Well

Saturday, June 1st, 2013This is my sixth article in a monthly series of articles about paintings that tell ancient stories, drawing from my Stories in Art project. Please click here for a full list of articles in this series.

~ § ~ § ~ § ~

After the death of Abraham’s wife Sarah (Genesis 23), the focus of the story shifts to the next generation: their son Isaac and his wife Rebekah. In Genesis 24, Abraham sends his most trusted servant to find a wife for our second patriarch, and that scene is the subject of one of my favorite paintings.

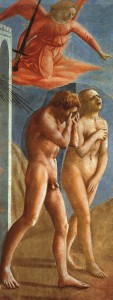

In 2007, when I started my Stories in Art project that forms the basis of this series of articles, I chose Nicolas Poussin’s Rebecca at the Well to feature in the site’s design. To me, this painting is a crystal clear example of a painting that makes a lot more sense once you know the story.

|

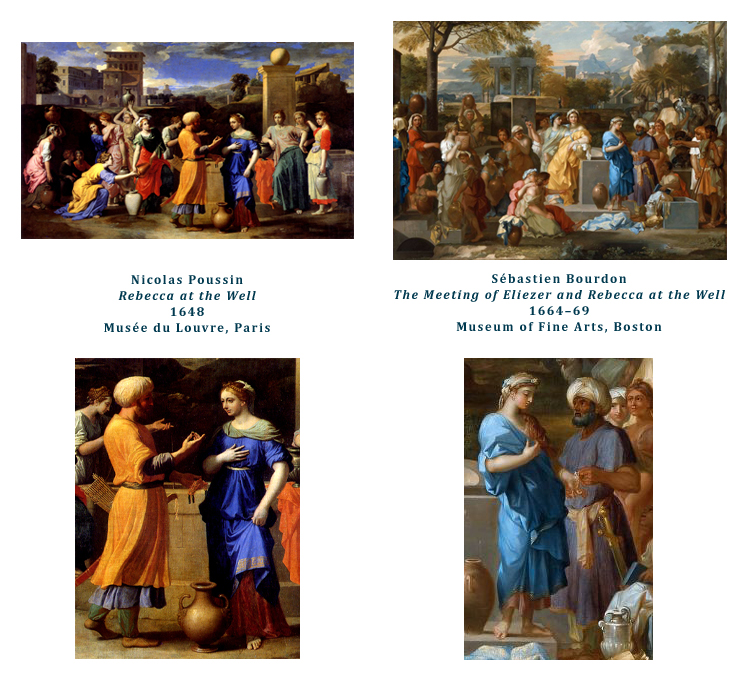

On the surface, it’s a fairly simple scene. A man approaches a group of lovely women, he speaks to the most beautiful woman, and offers her a gift, which she accepts graciously. It’s a pleasant scene and Poussin used this gathering of lovely women as an opportunity to show off his skills with flowing drapery and vibrant colors.

But if you know the story of Eliezer’s journey to find a wife for Isaac, the scene takes on new meaning. This may appear to be a commonplace scene of a man flirting with a beautiful woman, but it is in fact a scene of a loyal servant making an admirable decision. When Eliezer arrived at the well in Abraham’s homeland, he prayed to God to make his journey successful, and he asked that the woman he was searching for be the woman who offered to draw water from the well for his camels.

This is a quiet yet earth-shattering moment in the early chapters of our history. Eliezer could have asked God to show him the most beautiful woman, or the wealthiest woman, or the woman most likely to bear healthy sons, but instead, he asked God to help him find the kindest most generous woman to be our second matriarch. Eliezer valued kindness and generosity over beauty and wealth. If only we could all be a little more like Eliezer.

This is one of the only positive stories about a woman in the bible. Several thousand years before women were equal partners in relationships with men, stories about biblical women were about sexual violence, acts of desperation or innocent pawns among deceitful men. Refreshingly, the story of Rebekah at the Well is the story of how she was chosen to be Isaac’s wife because of her kindness and generosity. For this reason, I’m proud to be named Rebecca.

Of course, artists chose to ignore this rare positive message for women, and instead, spun the story to focus on our less flattering traits. After Rebekah offered water to Eliezer’s camels, Eliezer offered her gifts of jewelry and then asked to meet her family. By focusing on the moment when Rebekah accepts the jewels from Eliezer, artists made a selfless young woman appear vain and self-involved. In the case of Nicola Grassi’s gorgeous yet unfortunate painting on the right, she also appears rather smug and arrogant as she is singled out by the mysterious stranger. Click on the painting on the right to see more scenes like this.

This brings us back to Poussin’s scene, which also shows the moment when Rebekah accepts Eliezer gifts. One of the many reason I love this painting is because Rebekah appears far more humble in this scene than in Grassi’s. The wealthy stranger has disrupted the bustling daily scene of gathering water from the well, and for Poussin, this was a perfect opportunity to show his skills. Poussin was a master at designing a scene that is both busy and orderly, chaotic and balanced, scattered and focused.

To truly appreciate Poussin’s masterful composition, I have broken down the painting in to its parts to see how Poussin balanced warm colors with cool colors, while also balancing bold colors with neutral colors. Poussin leads our eye around this scene by following the gazes of the women and the direction of their arms. Please explore this composition by rolling your mouse over the categories below.

I would have to travel to Paris to see Poussin’s masterpiece in person, but I only have to walk around the corner to see a painting inspired by Poussin. Sebastien Bourdon was a brilliant French artist who studied Poussin and drew inspiration from his compositions. Bourdon’s painting of Rebecca at the Well hangs in the finest of the galleries at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Scroll down to see for yourself how Bourdon was inspired by Poussin.

~ § ~ § ~ § ~

Resources:

- Description of Nicolas Poussin’s Eliezer and Rebecca on the Musee du Louvre’s website

- Description of Sebastien Bourdon’s Eliezer and Rebecca on the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s website

- The Woman Who Named God: Abraham’s Dilemma and the Birth of Three Faiths, by Charlotte Gordon

- Rebekah, by Jill Eileen Smith

- Rebekah, by Orson Scott Card

- The God of Abraham, Rebekah and Jacob, by Moshe Reiss

~ § ~ § ~ § ~

More Articles:

Previous article: Abraham and Isaac | Next article – coming soon!