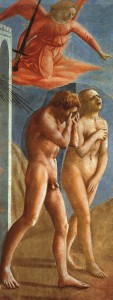

Guercino, Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael

This is my fourth article in a monthly series of articles about paintings that tell ancient stories, drawing from my Stories in Art project.

Please click here for a full list of articles in this series.

~ § ~ § ~ § ~

Abraham is the first common ancestor of the Jews, the Christians and the Muslims, and his stories in the bible are among the most fascinating and complex. In Genesis 21, the patriarch of three faiths finds himself caught between his wife, her maid, and their two sons. Abraham faced an unpleasant domestic dispute, and we are reminded daily of the dire consequences. What happened so long ago that we are still feeling the effects every day?

The Story of Hagar:

The Lord had said to Abram, “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you. I will make you into a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse; and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.” – Genesis 12:1

[The Lord said] “Look toward heaven, and number the stars, if you are able to number them … So shall your offspring be.” – Genesis 15:5

|

God promised that Abraham would be the father of a great nation, but after being married to Sarah for many years, they did not yet have a son. So Sarah sent her maid Hagar to sleep with her husband, hoping that “… perhaps I can build a family through her.” (Genesis 16:2). Hagar gave birth to Ishmael, and then God fulfilled his promise to Abraham and Sarah. They named their long-awaited son Isaac and one day, Ishmael mocked Isaac. Sarah insisted that Abraham send Hagar and her son away, and he did. Hagar and Ishmael wandered in the dessert and when their food ran out, God sent an angel to revive them and ensure their safety. Isaac became a patriarch of the Jews and Ishmael became the ancestor of the Muslims.

Before we get into the beautiful and troubling paintings that depict the rejection of Abraham’s first son, we’ll dig in to the decisions that led to the moment when the angel interceded.

Sarah’s Decisions:

Adriaen van der Werff, Sarah Bringing Hagar to Abraham, 1696, The Hermitage, St. Petersburg

God’s promise to Abraham in Genesis 12 (see inset above) forms the foundation of three major world religions, and yet, in those early chapters, one wonders how Abraham is supposed to have so many descendants if he doesn’t have a son. Ten years after they left their father’s household in search of the promised land, God had still not given Sarah a son. To ensure that Abraham would be a father, Sarah sent her maid Hagar to sleep with her husband.

Was Sarah selfless or desperate? Was she giving up on God’s promise, or demonstrating her true faith by ensuring that His promise would come to pass? When God shows us our destiny, should we sit back and wait for God to make things happen, or is it our job to fulfill our own destiny by taking action? This is not a simple question, but God helps those who help themselves and Sarah took matters in her own hands. Whether Sarah did the right thing or not, she set in to motion a chain of events that continues today.

Adriaen van der Werff summarized this complex situation by depicting this dynamic trio together in Abraham’s bedroom. Abraham and Sarah share a glance as if to agree on this course of action, while Hagar accepts her fate in an attitude that suggests passivity as well as piety.

Ishmael was born to Abraham and Hagar, and then years later, Isaac was born to Abraham and Sarah. Hagar’s son mocked Sarah’s son, and Sarah demanded that Hagar and her son be sent away so that Ishmael would not inherit along with her own son. Again, Sarah’s actions can be called in to question. Was she just being jealous and over-protective, or was she helping to fulfill their destiny by ensuring that Isaac, the rightful heir, inherited God’s promised land from his father.

Nicolaes Maes, Abraham Dismissing Hagar and Ishmael, 1653, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Abraham’s Decision:

Abraham reluctantly cast his firstborn son and his mother out of his household, denying them his protection and perhaps their survival. Was the father of three faiths a bad father? A parent’s duty is to protect and provide, but who would envy Abraham for having to choose between appeasing his wife and protecting his son? Abraham is not a bad father, and he dutifully kept the peace in his household by following the instructions of both God and his wife. God saved Abraham from having to make an impossible choice by assuring him that he was doing the right thing. In Genesis 21:11, God told Abraham to send Hagar and Ishmael away, and not to be concerned about them because He will make this son in to a nation as well.

In Nicolas Maes’ Dismissing Hagar and Ishmael, and other similar paintings, the expressions of the three characters tell the story plainly: Hagar is passive and disappointed, Ishmael is dejected and perhaps resentful, and Abraham is apologetic yet offers a gesture that suggests Ishmael’s blessing.

Paintings of angels interceding

on behalf of the sons of Abraham.

Guercino, The Angel Appears to Hagar and Ishmael, 1652-3, National Gallery, London

The text makes it clear that God protected and guaranteed a promising future for both of Abraham’s sons, but it also draws a sharp contrast between the favored son and the rejected son. While some artists reinforced the contrast between the sons, others drew attention to their similarities. By depicting the scene of the angel interceding when Ishmael was close to death, artists remind us of a similar scene in the very next chapter of Genesis when an angel will intercede to save Isaac’s life. We are reminded that God favored and protected both sons, and ensured that they would both live to fulfill their destiny of becoming the fathers of great nations.

Guercino’s painting in the London National Gallery depicts the moment when Ishmael was near death, and an angel arrived to point Hagar towards a well that would save their lives. His painting reminds us that God favored and protected Abraham’s outcast son Ishmael.

Giambattista Pittoni, Sacrifice of Isaac, c. 1720, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice

Many paintings such as Pittoni’s Sacrifice of Isaac depict the moment when Isaac was also near death and an angel interceded to save him. In both scenes, the artists highlight the crucial moment between life and death when the angel arrived to change the course of the story. God put both Ishmael and Isaac in a life-threatening situation, then sent an angel to intercede and save them. In seeing the connection between two scenes, we are reminded that God favored all of Abraham’s sons, not just the descendants of Isaac.

For centuries, hatred has grown between the sons of “the chosen one” and the sons of the outcast, and that hatred can be traced back to this story. Our present-day tragedies began with the rejection of an innocent woman and her son, but today’s situation is far more complex than the short verses of Genesis 21.

Am I really being too naive to hope that we can have peace if we can remember that God favored and protected both of Abraham’s sons, and not just one of them? Why must we focus on our differences when we have so much in common? If we knew the answer to this question then the last few millenia would have been very different.

~ § ~ § ~ § ~

In next month’s article, we will take a much closer look at paintings that depict ‘The Sacrifice of Isaac’: the moment when an angel stops Abraham from sacrificing his son. Until then, I leave you with a clip from a phenomenal episode of ‘The West Wing’, which was written and aired soon after September 11, 2001. In this episode, the White House is on lockdown because of a potential terrorist threat, and a school group is stuck at the White House. In this scene, the First Lady (Stockard Channing) tells them the story of Isaac and Ishmael in response to the question “How did all this start?” (beginning at 1:32 in this clip).

Clip from ‘Isaac and Ishmael’, Season 3 of ‘The West Wing’, written by Aaron Sorkin, first aired on October 3, 2001.

~ § ~ § ~ § ~

Resources:

~ § ~ § ~ § ~

More articles:

Previous article: Lot and his Daughters | Next article: Abraham and Isaac

Bela Lyons Pratt created two grand sculptures for the main entrance to the Boston Public Library. The sculptures depict Art and Science (this photo shows Art), and they are each displayed between pedestals inscribed with notable names from each field.

Bela Lyons Pratt created two grand sculptures for the main entrance to the Boston Public Library. The sculptures depict Art and Science (this photo shows Art), and they are each displayed between pedestals inscribed with notable names from each field.

Mrs. Gardner loved gardens, and in addition to her spectacular indoor courtyard, she included a lovely little outdoor garden just outside of her palace. When the museum’s annex was torn down to make way for the gorgeous new wing, the Monks Garden became a part of the construction site. Now, a year and a half after the new wing opened, the newly redesigned Monks Garden is finished!

Mrs. Gardner loved gardens, and in addition to her spectacular indoor courtyard, she included a lovely little outdoor garden just outside of her palace. When the museum’s annex was torn down to make way for the gorgeous new wing, the Monks Garden became a part of the construction site. Now, a year and a half after the new wing opened, the newly redesigned Monks Garden is finished!

It was a madhouse at the MFA today. Gorgeous day, the semester’s almost over, the terrorists have been caught, the Samurai exhibit just opened, the Michelangelo exhibit just opened, and Art in Bloom is happening. For three days, gorgeous floral displays are placed throughout the galleries near the work of art that they were designed to be displayed with. They’re absolutely gorgeous, and it draws a huge crowd. In fact, I left just as a huge school group was arriving.

It was a madhouse at the MFA today. Gorgeous day, the semester’s almost over, the terrorists have been caught, the Samurai exhibit just opened, the Michelangelo exhibit just opened, and Art in Bloom is happening. For three days, gorgeous floral displays are placed throughout the galleries near the work of art that they were designed to be displayed with. They’re absolutely gorgeous, and it draws a huge crowd. In fact, I left just as a huge school group was arriving.

I had a cold last week, which kept us from seeing the MFA’s new Samurai exhibit during the Members’ Preview days. We finally got the chance to see it tonight, and it was spectacular! When it comes to art, ancient Japanese armor is far from my usual favorites, but this is an exquisite collection of truly magnificent craftsmanship. Brian loves this kind of stuff and we were both really excited to see this exhibit.

I had a cold last week, which kept us from seeing the MFA’s new Samurai exhibit during the Members’ Preview days. We finally got the chance to see it tonight, and it was spectacular! When it comes to art, ancient Japanese armor is far from my usual favorites, but this is an exquisite collection of truly magnificent craftsmanship. Brian loves this kind of stuff and we were both really excited to see this exhibit.

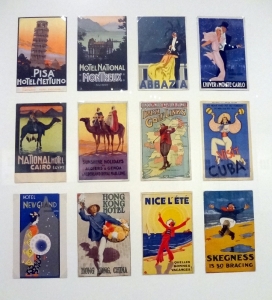

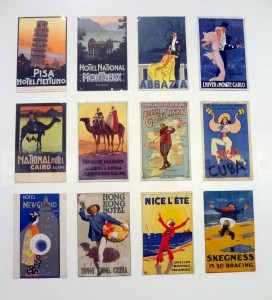

The Postcard Age

The Postcard Age